Halt Extraction Design Studio

1003 lausanne,

Suisse

Publié le 18 juillet 2025

EPFL ENAC-DO

Participation au Swiss Arc Award 2025

Données du projet

Données de base

Données du bâtiment selon SIA 416

Description

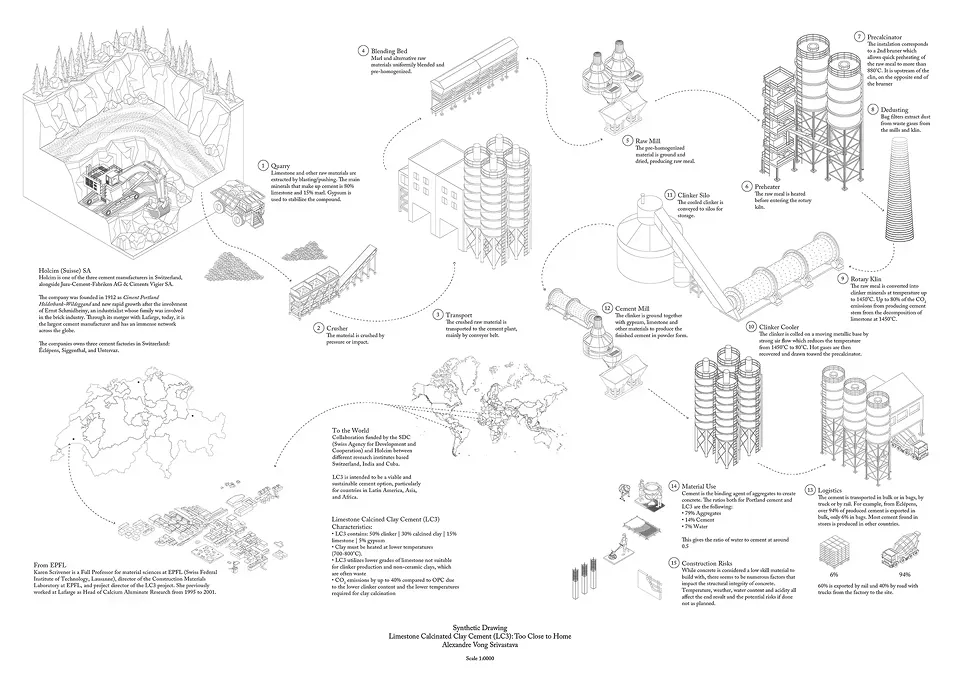

The design studio took place during the Spring Semester 2025 (17 February – 27 May) at EPFL ENAC IA, under the direction of Prof. Dr. Charlotte Malterre-Barthes. It was part of the «RIOT» (Research and Innovation On Territory) lab and was supervised by Elif Erez-Henderson, Antoine Iweins, Kathlyn Kao, Carolina Pichler, and Eva Oustric. The following students participated in the studio: Colin Baumgartner, Nicolas Cattin, Tamara Khalil, Michelle Lepori, Costanza Mizahi, Eva Pere, Marwan Abansir, Ben Begon, Alex Collet, Arthur Douillet, Leo Duyck, Auriane Farine, Eddy Fridli, Nicolas Gemelli, Lydia Genencad, Raul Hansra, Helen Herget, Yasure London, Esteban Lorenzo, Valerie Maillard, Julien Nicod, Alexandre Srivastava Vong and Gabriel Treyer.

Nota bene: This studio is part of the «Moratorium on New Construction» cycle, one of the «RIOT» lab’s meta agendas, following topics seeking to center systemic change in architecture and the building industry. The class prioritizes radical designs that engage with repair, remediation, care, tactical interventions, system design and policy making, and interrogate architecture as the sole «art of building buildings». Architecture is here at the forefront, considered both as a problem but also as a powerful tool for change, if and when it is used as such.

«You know that we are living in a material world», Madonna, Matthew E. Marston / Paul Christopher Brown, Sony/atv Songs L, Imagem Publishing.

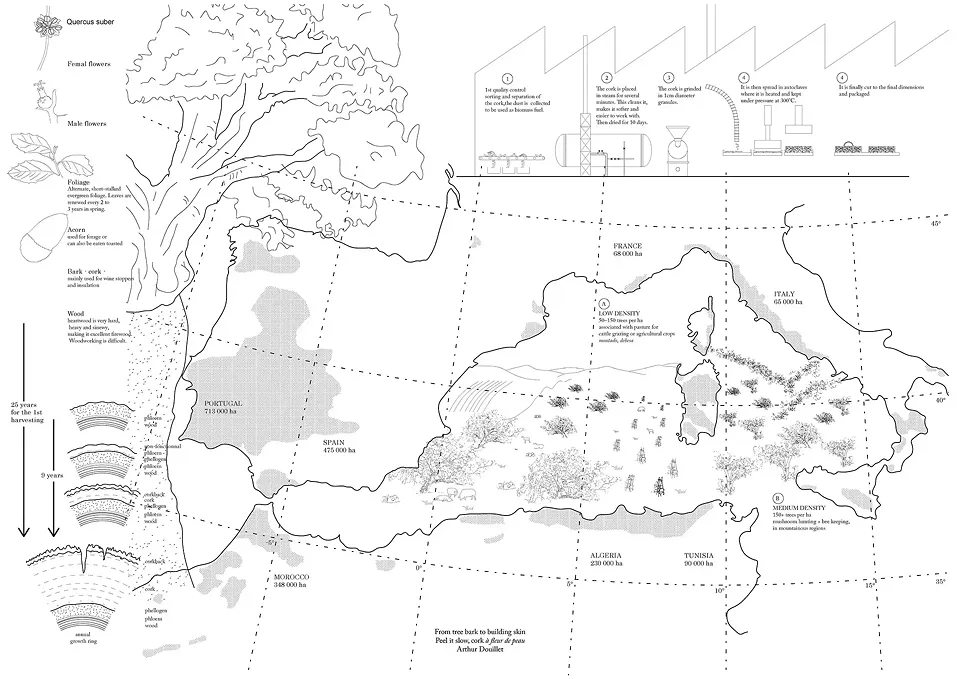

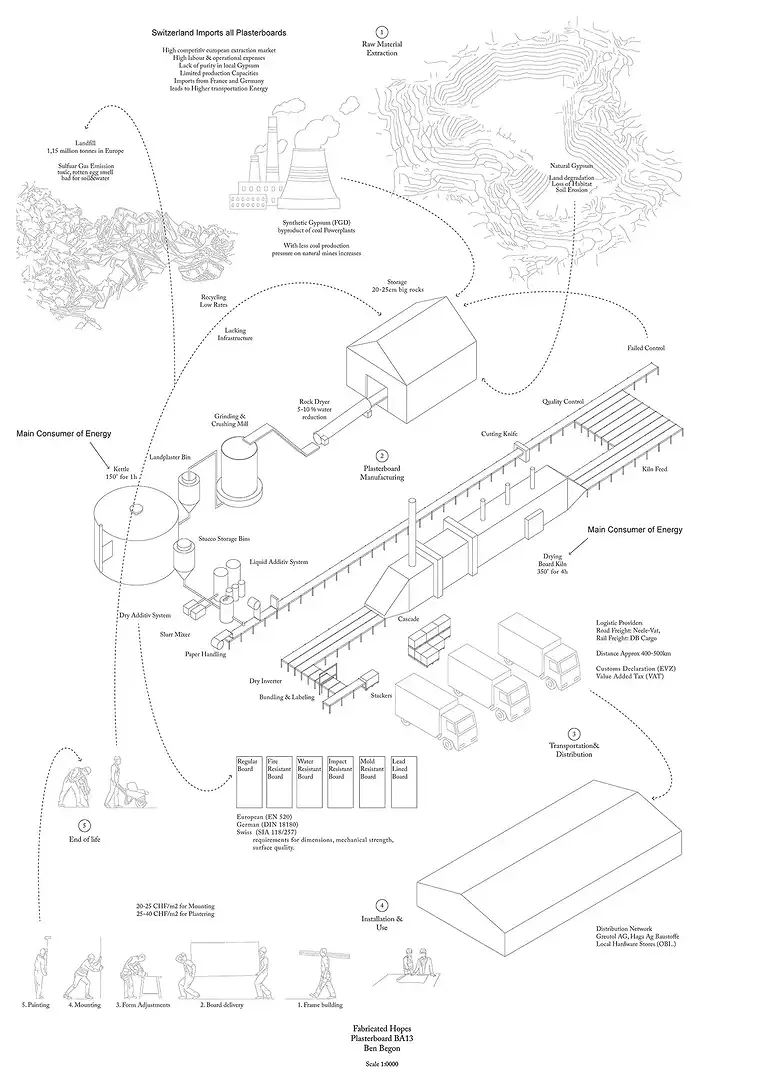

«Halt Extraction» scrutinizes the intersection of design disciplines with extractivism and resource exploitation, focusing on developing post-extractive architectural and urban design strategies. The studio investigates how construction materials transform the Earth’s resources into our built environment through global and local supply chains, and how design can contribute to post-extractive architectures. Grounded in arguments explored in the forthcoming book «A Moratorium on New Construction», we seek to address the political problems of construction as designers.

The course progressed through two main phases:

-

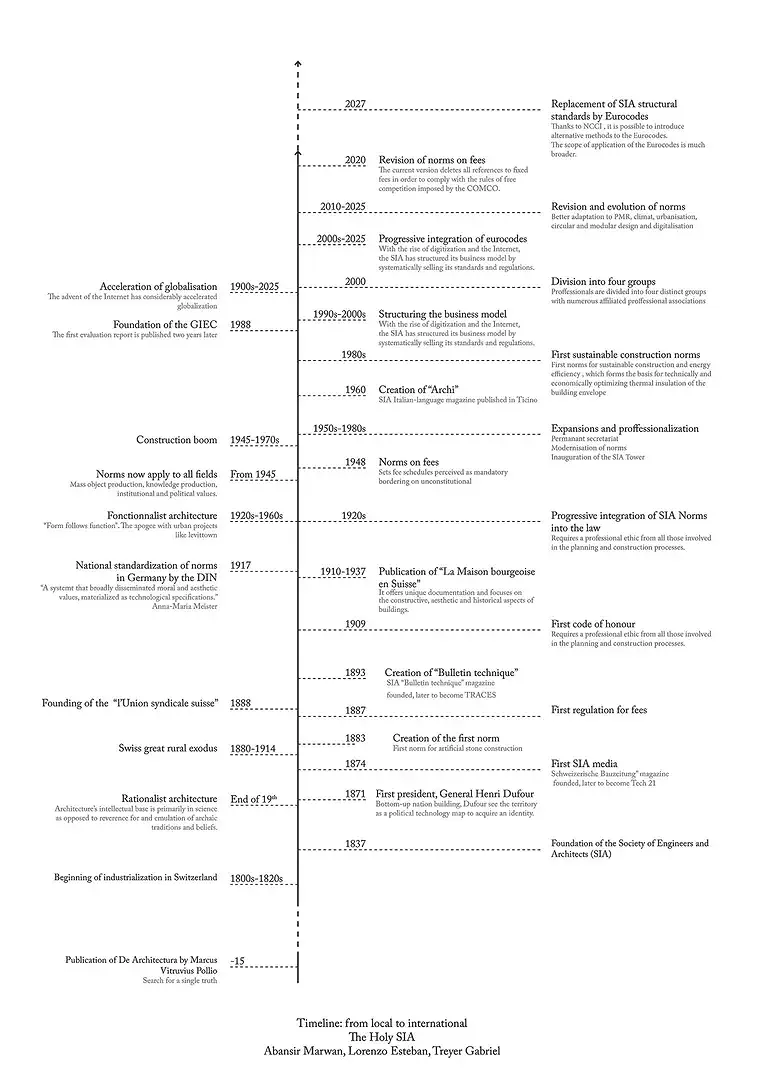

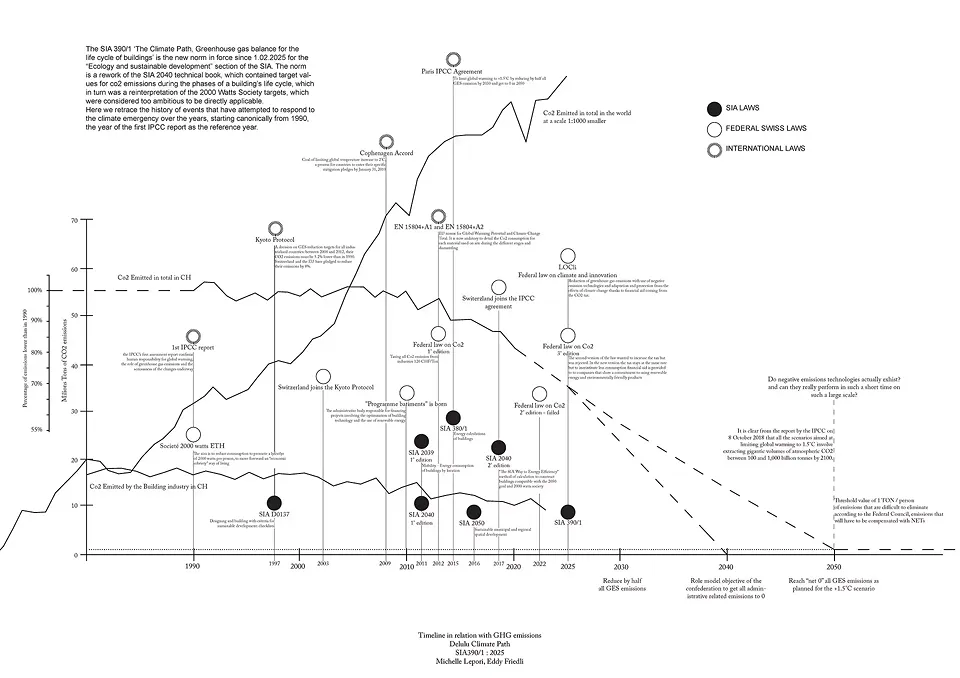

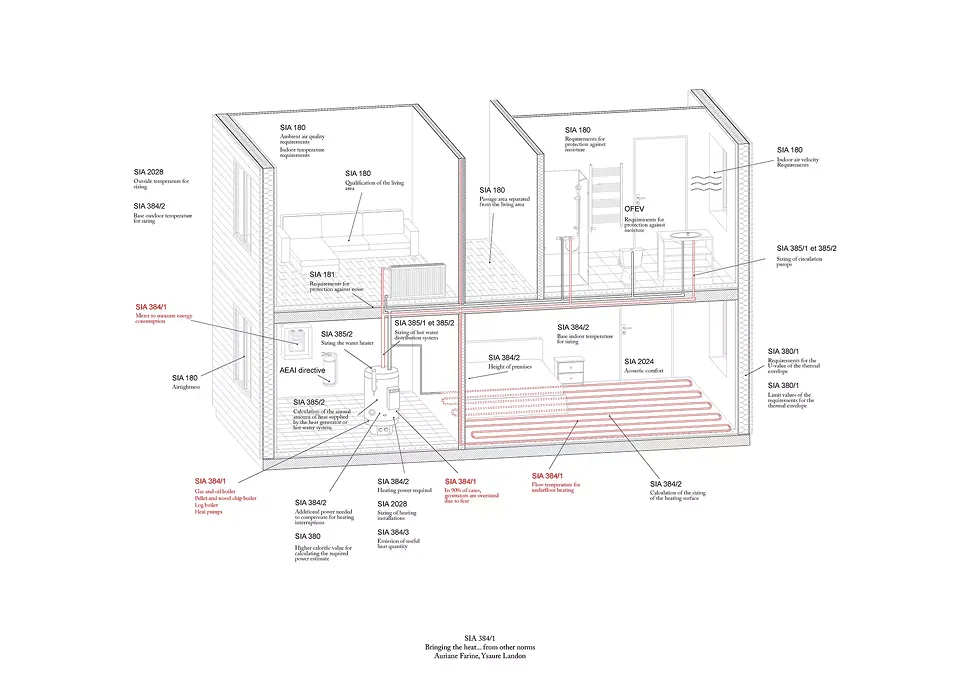

The research phase establishes a comprehensive understanding of how design disciplines intersect with extractivism and resource exploitation through mapping the global and local chains of construction materials and uncovering the normative systems in place that regulate their use in design strategies. By investigating construction materials (that is to say, plaster, wood, concrete, brick, steel) and their political economy (how value is extracted from them), we unpack how the industry translates the Earth’s resources into our built environment. We then seek to understand the normative regulations, specifications, and legal frameworks that dictate how these materials are deployed in construction, such as SIA norms.

-

Framed by these regulatory limits and equipped with critical thinking, we devise design strategies that do not rely on destruction and exhaustion to produce spaces. During the design phase, building on this foundation, we engage with existing structures (that is to say, La Rasude, Lausanne) rather than defaulting to new construction, using current market conditions as testing grounds for alternative approaches.

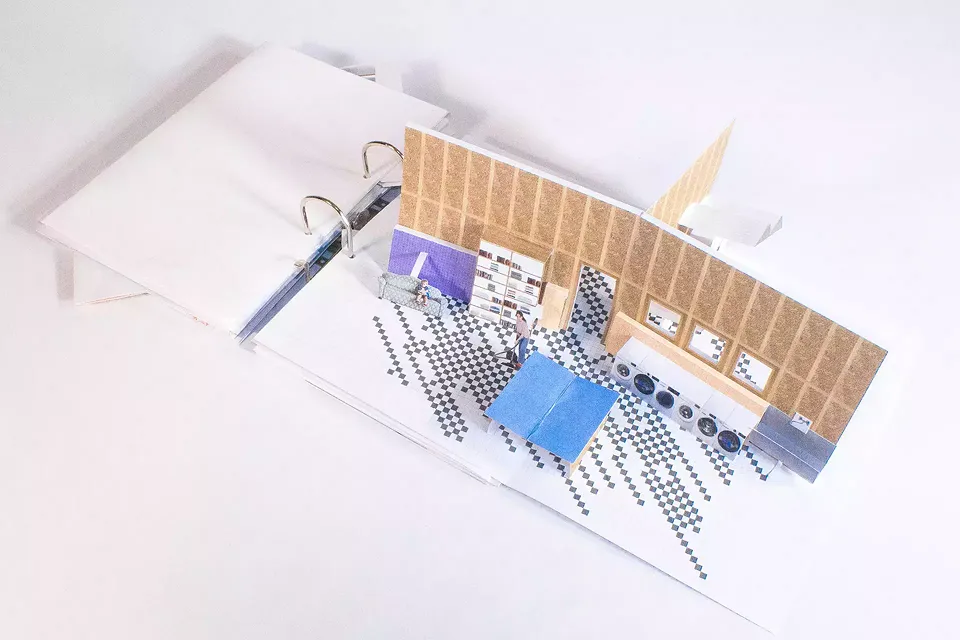

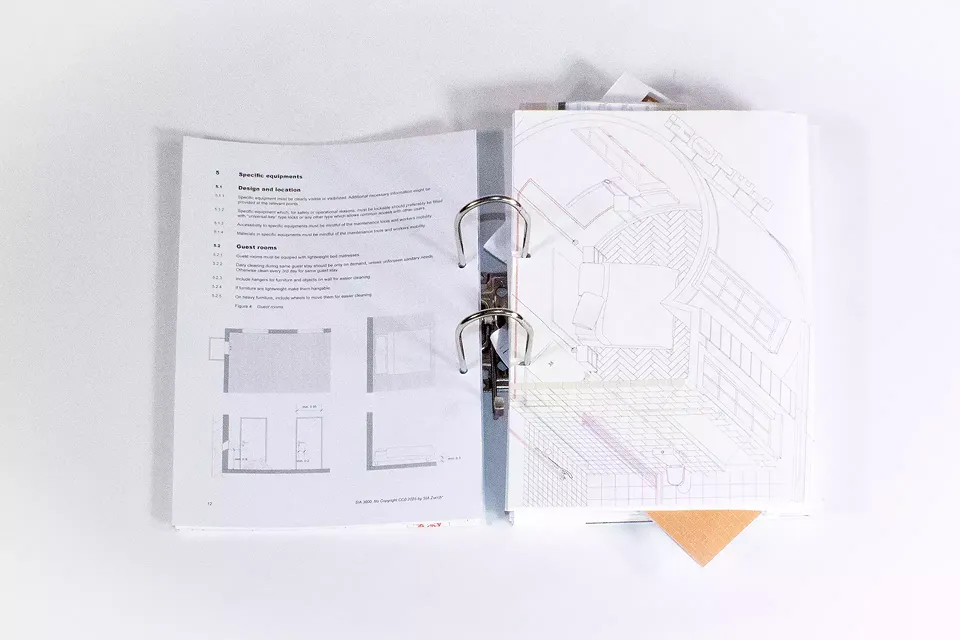

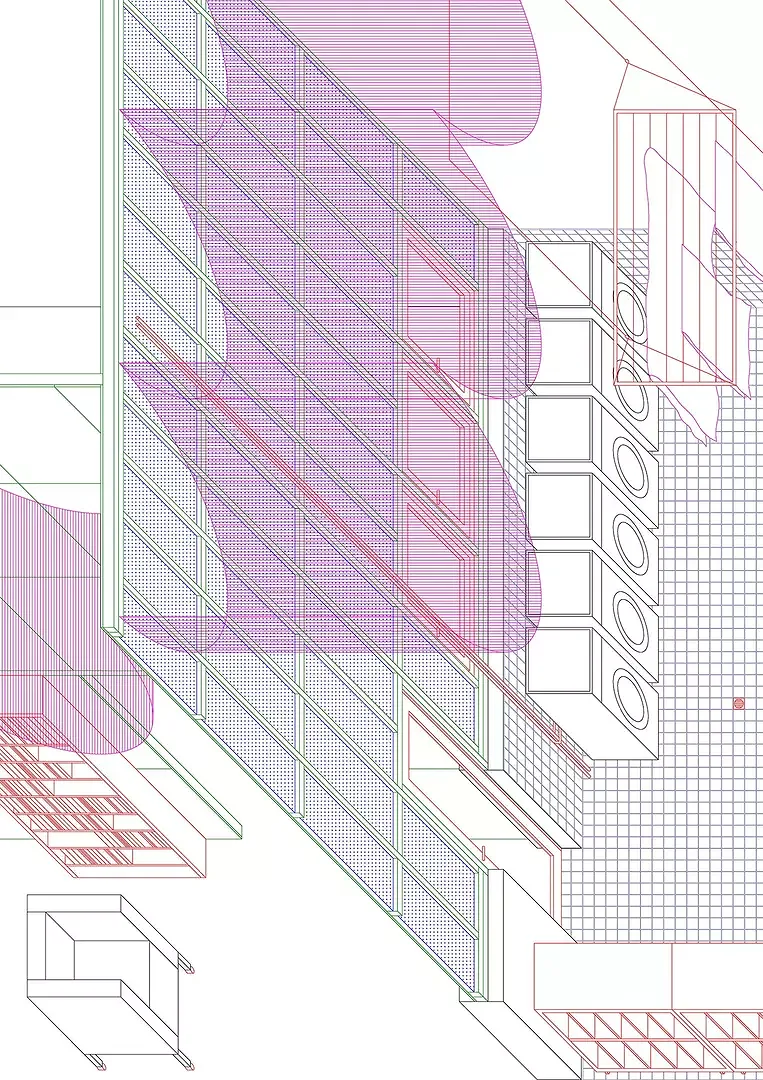

Choreographed by episodes that set the tone both graphically and analytically, the studio explored the complex networks of material extraction, supply chains, and construction practices that shape our built environment. Students were asked to engage with construction materials, their origins, and the normative systems that regulate their use. Investigating material lifecycles, from extraction sites to architectural applications, we produced works in various formats (that is to say, diagrams, drawings, supply chain maps, and material documentation) that helped us understand and articulate the interconnections between Earth’s resources, global trade, and architectural production. While engaging in this research, we gained literacy in material specifications, building codes, environmental regulations, and the political economy of construction materials in order to draft and draw strategies for post-extractive architectural interventions. The studio articulates design as the product of geological, environmental, economic, and political mechanisms while seeking to imagine futures liberated from destructive construction practices. Traditional architectural representation methods will be employed (that is to say, plans, sections, models) but reframed through the lens of material origins and impacts. Episodes were paced across the semester with a counter-crescendo, first rapid and later slowing down to let the project emerge.

In parallel, the studio also conducted a self-critical reflection on its format to question architecture’s attachment to solutionism, the expectation to «fix problems», and other tropes that have led to socially and spatially unjust situations. It acknowledges the limitations of critique within a discipline which has not faced its complicit role in the current climate and social crisis. We are aware that seeking engagements with actors and communities within the given format of the studio is limited. Yet within these given limits, we strive to produce works that have pedagogical value beyond the expected formats.

In the framework of Bruno Latour’s question, «Where to land?» («Où atterrir?»), or rather: «What are our options for reinventing a shared world?», students were asked to consider the following questions: Who do we work for?; How do we locate ourselves in the construction industry constellation?; What do we agree to do and not to do?; How can we build/unbuild differently?; What does architecture look like when prioritizing regeneration over depletion, repairing, or undoing?; What existing resources can we tap into?; What are the forms and the aesthetics of these responses? [1] Beyond individual materials and norms, they questioned the very premises of our design processes: How might we reorganize construction to minimize new extraction? Can we design harmless supply chains that collaborate «with flows and cycles» of materials? What if we thought design interventions as material banks for future use? What cultural and economic shifts are needed to support these changes? How can we design buildings that heal rather than harm? What new tools, methods, and collaborations do we need? What is the architect’s role in catalyzing systemic change in the construction industry?

For the final episode of the studio semester, Design without Extraction, we used La Rasude, in Lausanne, partially slated for demolition, as our test site.

Strategically located, La Rasude district is situated on a triangular plot of land framed by Avenue de la Gare at the north, Avenue d’Ouchy at the east, and the train tracks to the south. Immediately to the west is the expanding Lausanne train station that handles upwards of 140 000 riders daily and is the main northern transportation entry to Canton Vaud, and the museum complex platform.

Today, La Rasude’s six buildings are home to the Swiss Post office, the CFF administrative hub, and other auxiliary programming. In 2014, La Rasude’s owners, Mobimo and CFF Immobilier, in partnership with the City of Lausanne, issued a parallel study mandate for a new mixed-use district that would be initiated by a partial allocation plan in 2020. The master plan competition was won by EMA Architects. The new urban development programming included the preservation of the buildings Avenue de la Gare 41–43 by Swiss architect Alphonse Laverrière, the 1960s Horizon building along Avenue d’Ouchy, and new buildings, towering 13 stories, that will include: 65 percent offices, 20 percent residential, 8 percent hotels, and 7 percent commercial, with additional public space development. In sum total, this corresponds to 76 000 square metres of floor area.

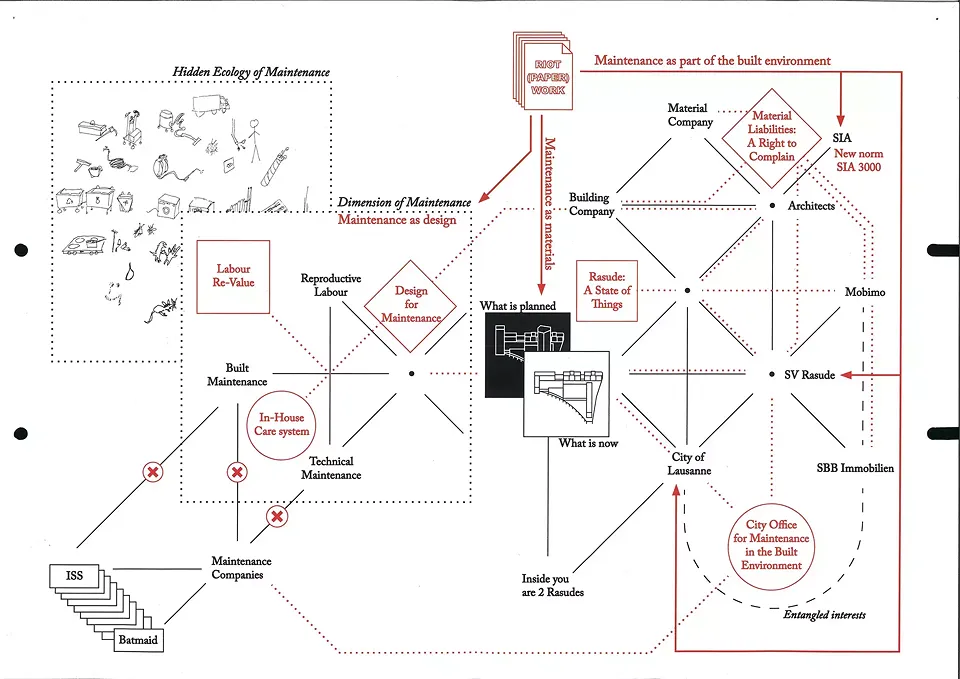

In order to challenge this future envisioned for La Rasude, we first gained a basic understanding of the site; the actors engaged (that is humans, non-humans, legal, financial, economic, social, institutional, and environmental forces), acquainting ourselves with the spatial forms and elements of the built and unbuilt environment of the site (above and below ground, built mass, existing square metres, and so on). Officially, it is argued that «the relatively small proportion of housing is restricted by the site’s constraints, particularly the need to comply with federal regulations on protection against major accidents and noise.» Framed by regulatory limits and equipped with critical thinking, we worked towards devising design and material strategies that do not rely on destruction and exhaustion to project a vision «to imagine, engender, and enact worlds otherwise.» [2]

While at times destabilizing, the studio aims to challenge the design processes we tend to follow (program > design > material) and shift priorities (program > material > design). The studio drew inspiration from local material networks and virtuous precedents — exploring collective, less extractive, revolutionary lifestyles, repair cultures, urban mining, material reuse, bio-based and regenerative materials, and low-carbon traditional knowledge in creating resilient, non-extractive building practices. Building upon the «Moratorium on New Construction» call that «the radical change required is to completely discard extractive value systems as the guiding compass toward «progress», rather than just transferring them in an “ethical” way, redemptive value is ascribed to those systems with lighter footprints, non-extractive socialities, and ethical principles as the way forward.» [3] La Rasude is perfect because «existing buildings are a resource for creating affordable and habitable spaces—while listening to anthropologist Arturo Escobar’s plea for architecture to deliver “new modes of earthly habitation (…) changing the practices that account for our dwelling in ways that enable us to act futurally instead of insisting on the strategies of adaptation to defuturing (future-destroying) worldly conditions that are on offer at present.» [4]

At the conclusion of the studio, seven alternate futures of La Rasude addressed themes of the commons, housing, non-sexist cities, maintenance and care, remediation, and demolition, that when taken in sum deconstruct the paradigm of «urban redevelopment» and «demolition/reconstruction» and all the growth narratives.

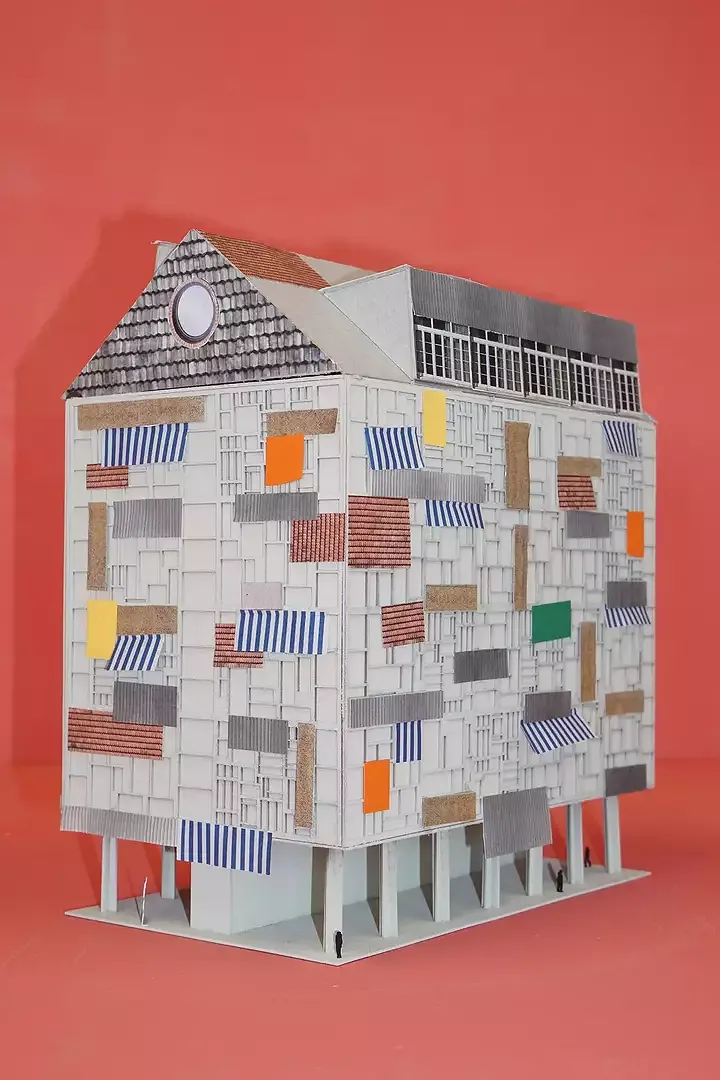

Selected Projects

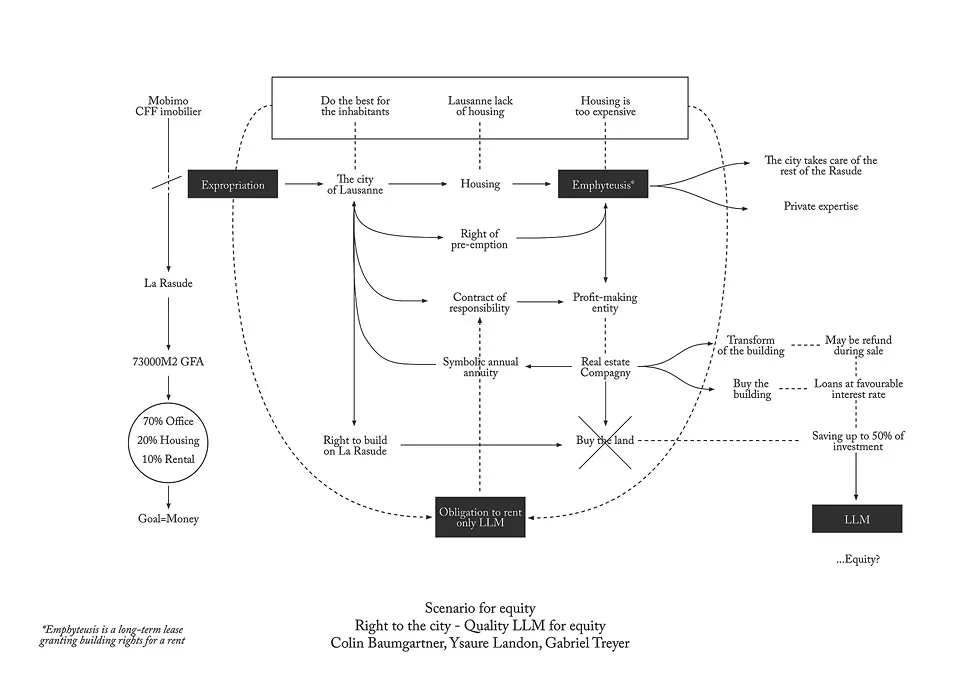

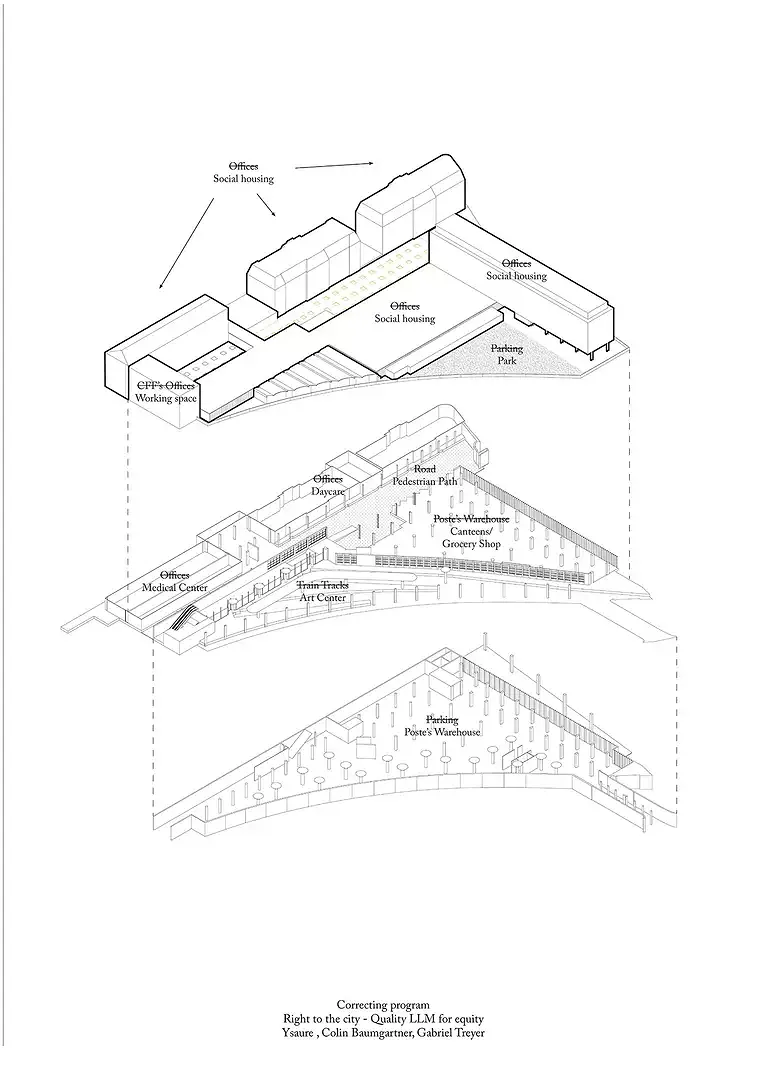

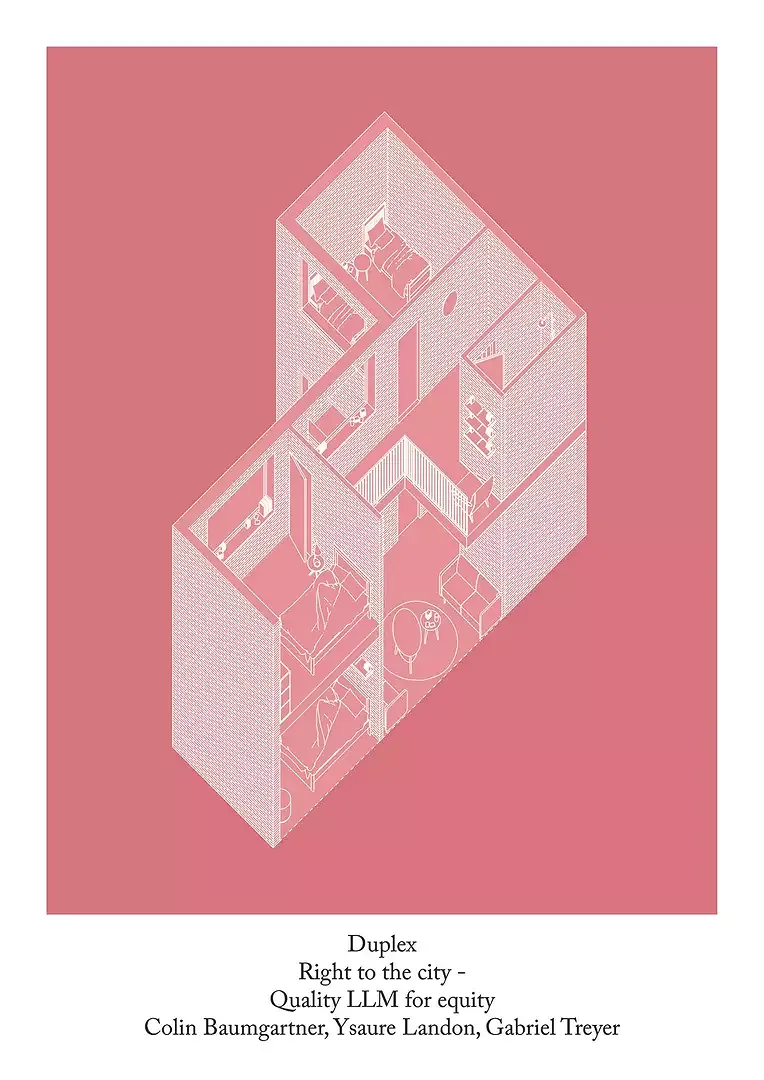

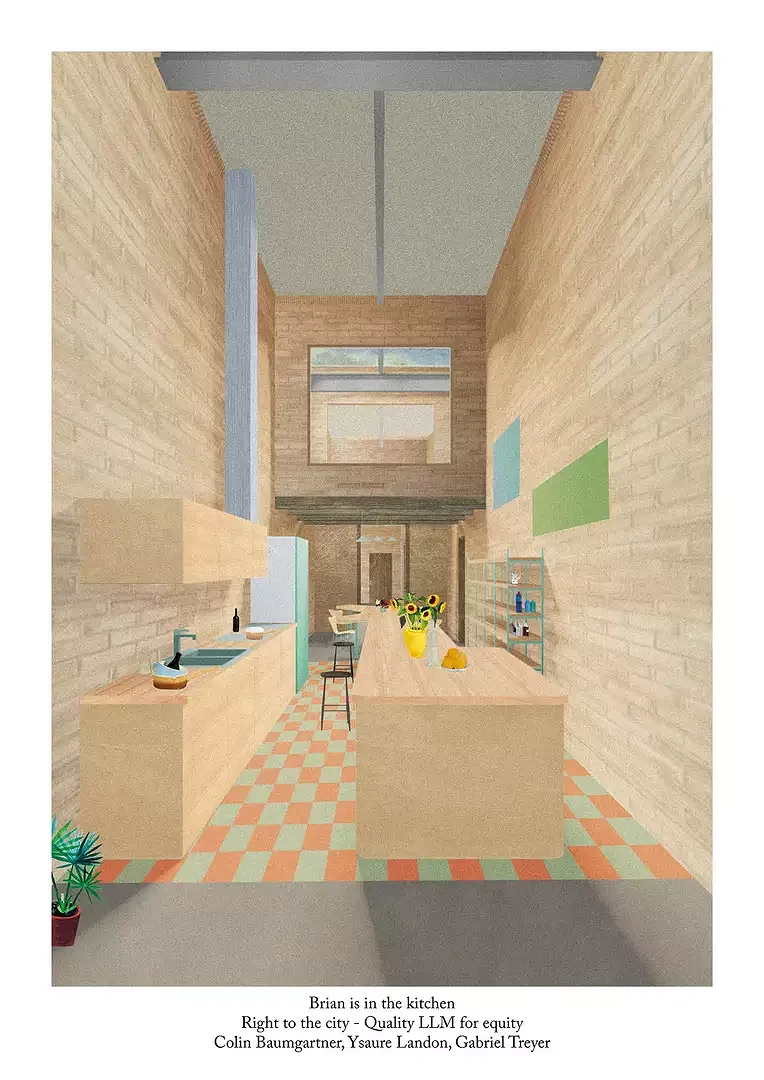

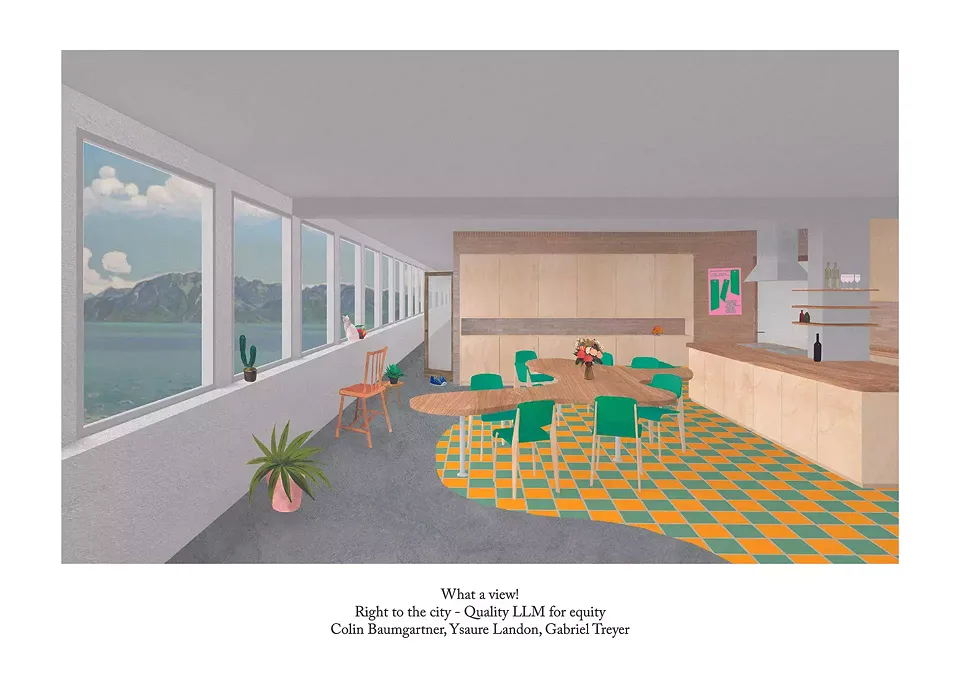

The student group, «Right to the City», in direct reference to Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey, calls attention to the inherent contradiction in Mobimo and CFF Immobilier’s plan to allocate 70 percent of La Rasude to offices, 20 percent to housing, and 10 percent to retail – despite Lausanne’s pressing need for affordable housing, not office spaces. Arguing that the city intentionally sequesters public housing to its periphery, thus reinforcing patterns of spatial injustice, the project proposes three adaptive reuse housing that emphasize material honesty and quality of living. The design reveal the site’s latent potential as a location for central affordable housing and demonstrate how thoughtful densification – without new construction – can counter Mobimo and CFF’s argument that market demands necessitate building anew.

In «Matter of Care», SIA Norm 3000 is revised to place maintenance and care at the center of architectural responsibility, arguing that, at its core, architecture is an act of care. Yet conventional practice glorifies the autonomous architect and heroic design, sidelining the continuous labor of maintenance. Buildings come to life only through ongoing repair, cleaning, and adjustment – work carried out by invisible and undervalued hands. La Rasude becomes a testing ground where lived building experiences inform regulatory norms, and care practices and materials are actively explored. This reciprocal process affirms the spatial rights of care workers and introduces alternative systems of maintenance into conventional architectural programs..

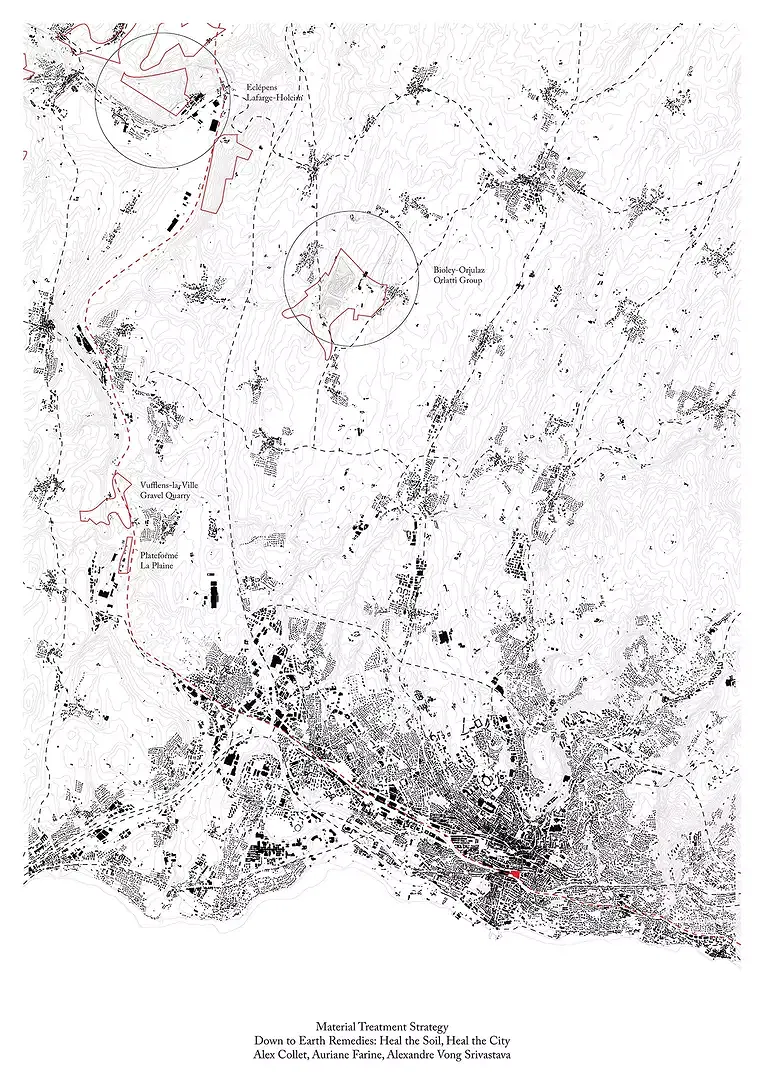

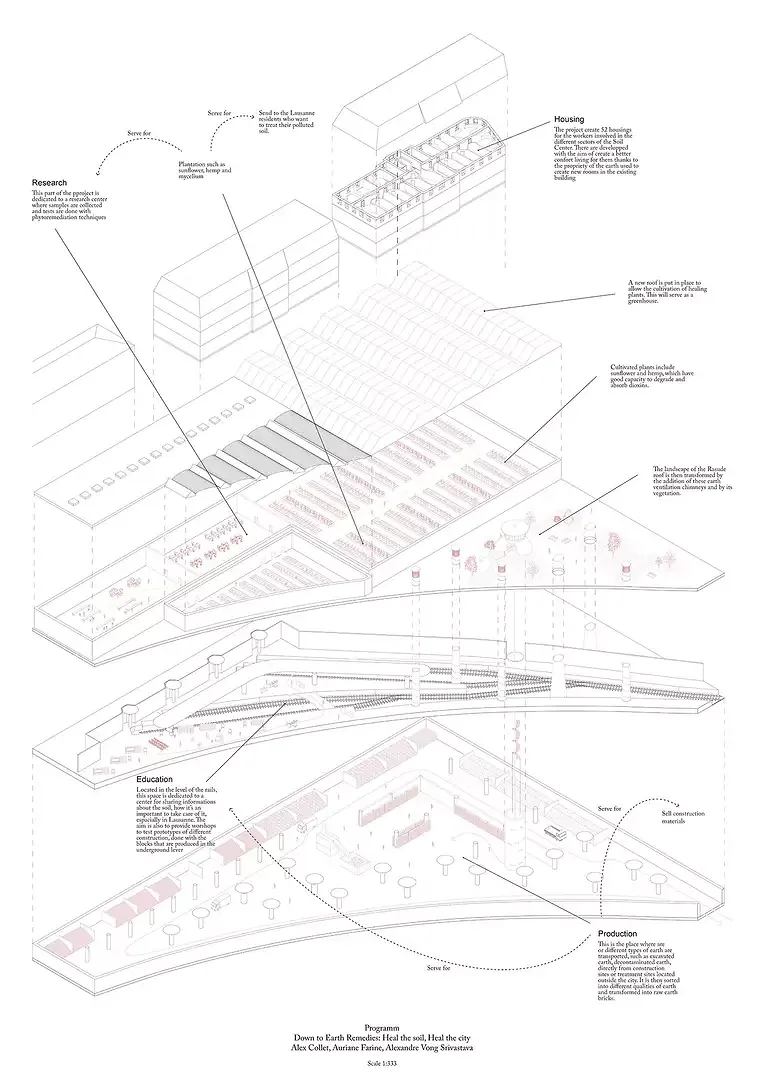

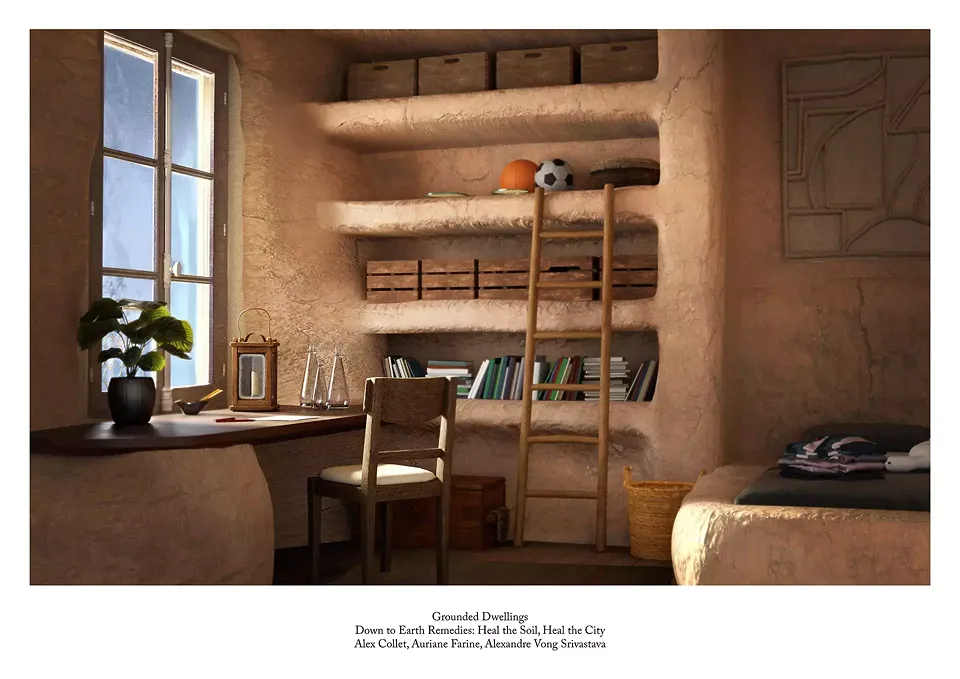

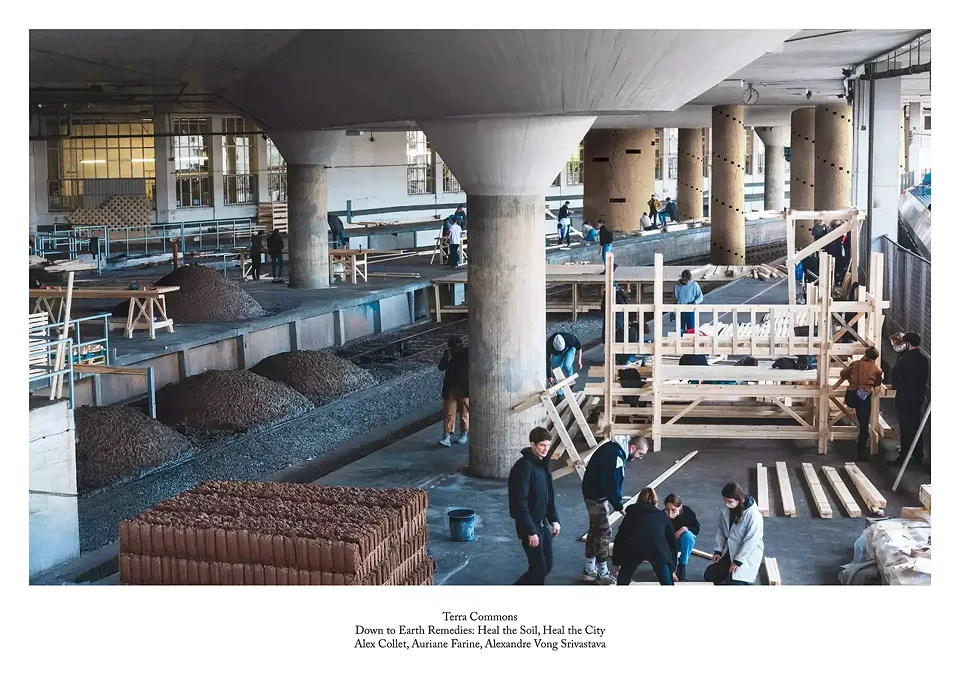

«Down to Earth Remedies» reimagines La Rasude’s critical location as a nexus that contends with the city’s storied history of industrial contamination that still pervades through its soil today. Responding to the 2021 report that exposed 85 percent of Lausanne’s dioxin-polluted soil that requires remediation, 16 percent of which exceeds acceptable thresholds targeting first locals whose playgrounds remain toxic and gardens unusable, the group proposes La Rasude to be in service of its inhabitants, and restore what is rightfully theirs — healed soil. Their work replaces offices, commercial and hospitality programming with soil remediation logistics, research, analysis, and then expands outwards first, offering a strategic pathway with commensurate space and materials for citizen soil processing rights, and then towards the city’s periphery for soil processing. Once the soil is safe, it can generate non-toxic building materials, creating a regenerative cycle. Through healing soil, they work to heal the city.

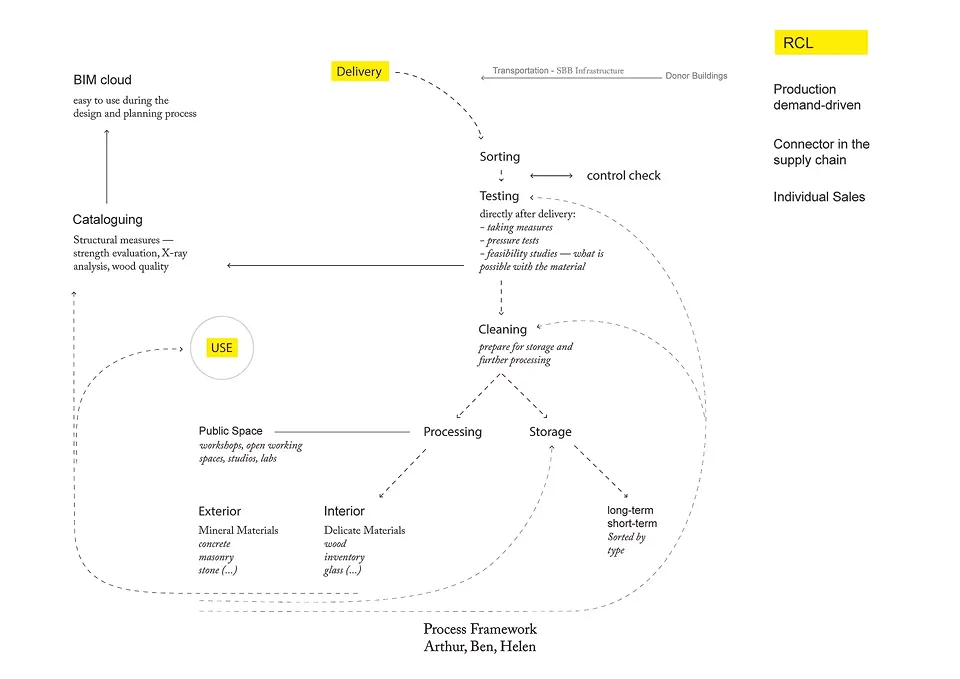

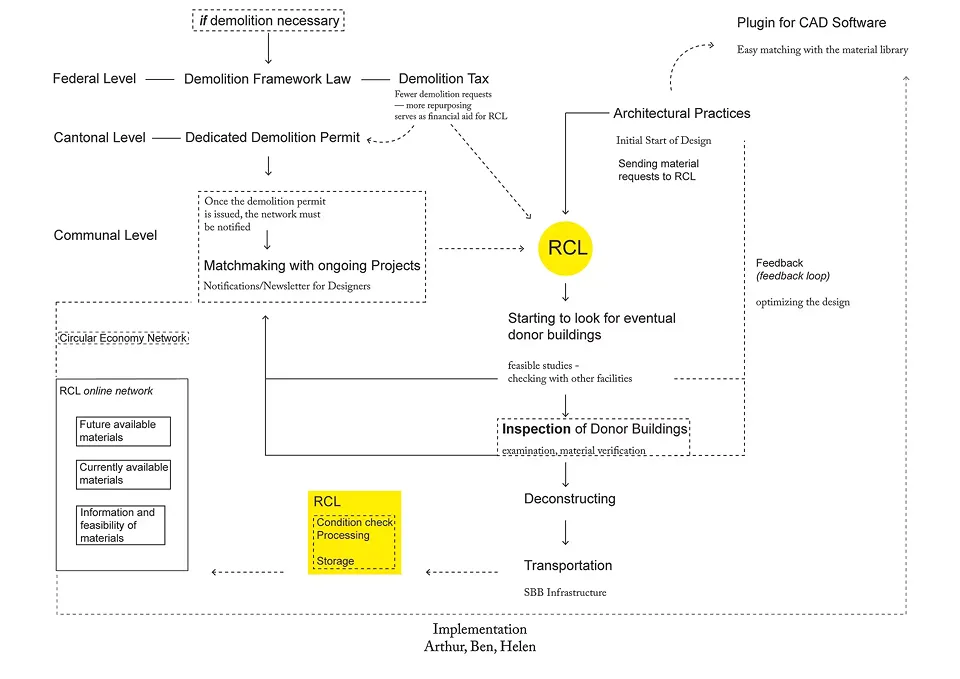

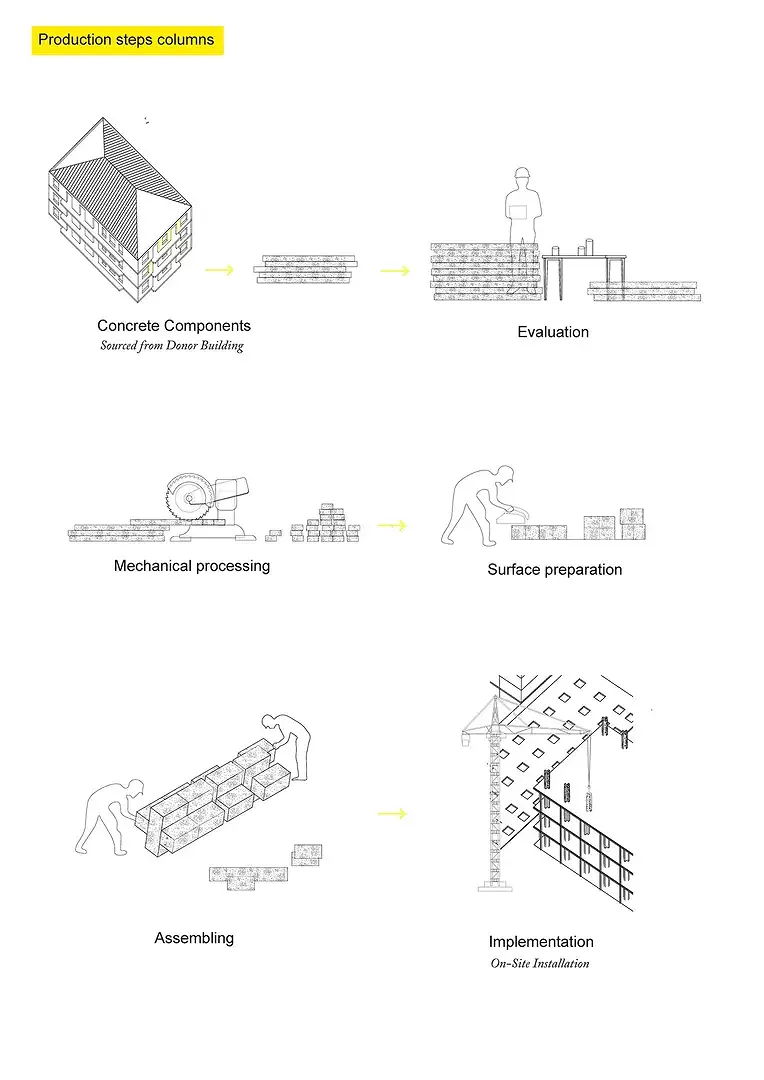

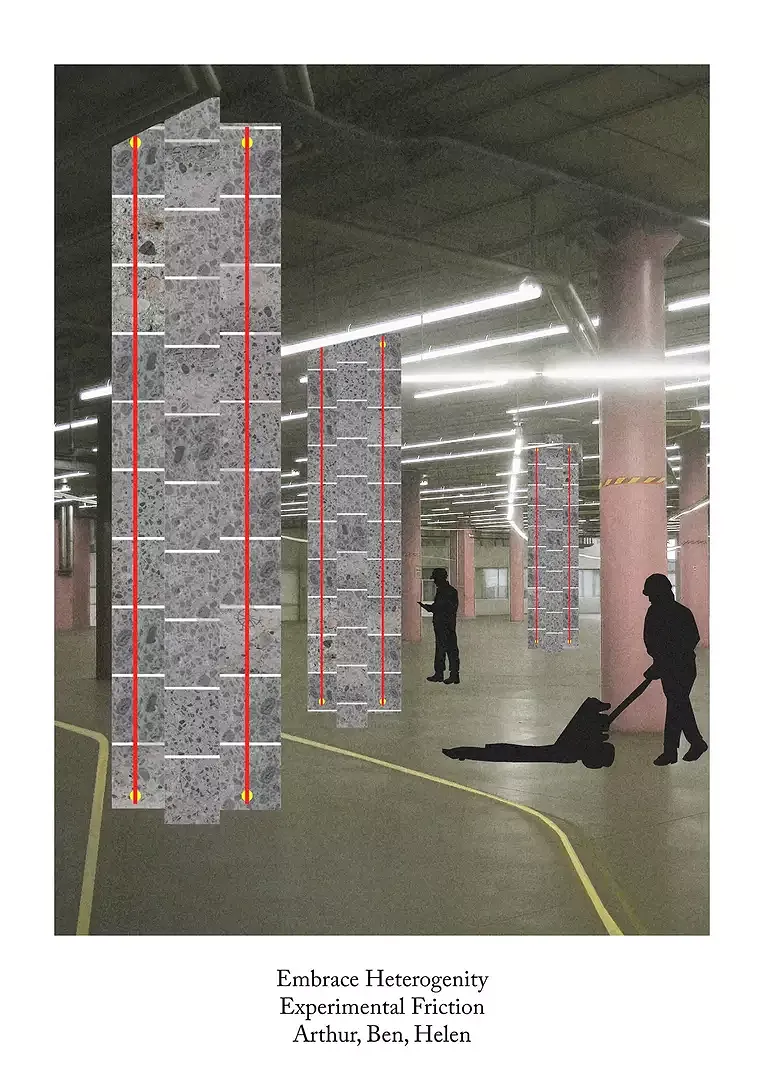

Another project, «Experimental Frictions» departs from a different, but equally critical fact: 70 buildings in Lausanne will face demolition, condemning precious materials to landfills. They ask, what if demolition stopped altogether? Demolition permits become disassembly permits — requiring full material assessment and cataloguing. The group capitalizes on La Rasude’s 76 000 square metres to bridge this new disassembly culture with construction, developing a circular material economy and a testing ground for new structures made of existing elements. The SBB logistics network thus morphs into a non-extractive national supply chain, redistributing reclaimed materials, and new potentials for heterogeneous assemblies emerge.

Bibliography

-

Arboleda, Martin. Planetary Mine : Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism. Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2020.

-

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter : A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010._A Life of Metal

-

Coole, Diana and Samantha Frost, eds, New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency and Politics, Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010

-

Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspectives” in Feminist Studies (1988) 575–599.

-

Demos, T. J. Beyond the World's End: Arts of Living at the Crossing, Edited by collection e-Duke books scholarly. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

-

Eskilson, Stephen. The Age of Glass : A Cultural History of Glass in Modern and Contemporary Architecture. London ; New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, an Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2018.- Structural Glass p 121-159

-

Förster, K 2022, ‘Triangular Stories: Cement as Cheap Commodity, Critical Building Material, and a Seemingly Harmless Climate Killer.’ in FHNW - Institut Architektur, A Helle & B Lenherr (eds), Beyond Concrete: Strategies for a post-fossil Baukultur. Triest Verlag, Zurich, pp. 35-65.

-

Hutton, Jane. Material Culture: Assembling and Disassembling Landscapes. Berlin: Jovis Berlin, 2018. p236-251

-

Ibañez, Daniel, Jane Elizabeth Hutton, and Kiel Moe. “Wood Urbanism : From the Molecular to the Territorial.” New York: Actar Publishers, 2019. p47-63

-

Lloyd Thomas, Katie. ed., Material Matters: Architecture and Material Practice (London: Routledge, 2007);

-

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone : Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017)

-

Malterre-Barthes, Charlotte. A Moratorium on New Construction (Berlin, London: Sternberg Press/MIT Press, 2025).

-

Marcuse, Peter. "Sustainability Is Not Enough." Environment and Urbanization 10, no. 2 (1998).

-

Material Cultures, Material Reform : Building for a Post-Carbon Future, First edition. (London: MACK, 2022)

-

Moe, Kiel. Insulating Modernism, Physiology, Insulation, Climate and Pedagogy. 189-227

-

Ouassak, Fatima. Pour Une Écologie Pirate : Et Nous Serons Libres (Paris: La Découverte, 2023) 76-93

-

Stead, Naomi ed. (2012) “Special Issue: Women, Practice, Architecture” in ATR (Architectural Theory Review), (Issues 2-3, Vol. 3).

-

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

-

Welland, Michael “Sand: The Never-Ending Story.” Berkeley, LA: University of California Press 2010). Chapter : Individuals: Birth and Character. pp1-30

-

Woudhuysen, James. Why Is Construction So Backward?, Edited by Ian Abley. Chichester Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Academy, 2004.

Endnotes:

[1] Latour, Bruno, Où Atterrir? : Comment S’orienter En Politique. ed. Paris: La Découverte, 2022.

[2] Serafini, Paula. Creating Worlds Otherwise: Art, Collective Action, and (Post)Extractivism.: Vanderbilt University Press, 2022.

[3] Malterre-Barthes, Charlotte. A Moratorium on New Construction. Critical Spatial Practice. London, Cambridge: Sternberg Press, MIT Press, 2025.

[4] Id.

The project by the EPFL ENAC IA Research and Innovation On Territory (RIOT) was submitted for the Swiss Arc Award 2025 in the Next Generation category and published by Nina Farhumand.