Hétérotopies 95200

95200 Sarcelles,

Frankreich

Veröffentlicht am 18. Juli 2025

EPFL ENAC-DO

Teilnahme am Swiss Arc Award 2025

Beschreibung

The design studio took place in the Spring Semester 2025. It was conducted as part of the TEXAS professorship, led by Eric Lapierre, and supported by Thibaut Pierron, Tanguy Auffret-Postel, and Mathilde Thiriot. The following students participated in the studio: Attis Bijleveld, Tom Liechti, Matteo Descouedres, Stan Caraz, Axel Bouy, Pierre Verhellen, Salma Tarbush, Medea Zullino, Thomas Albanesi, Christian Kalmus, César Mouly, Delphine Dam Wan, Joanne Fahrni, Célia Barman, Marta Ruta, Flavio Silvestri, Apolline Viet, Axel Guérin, Youssef Kali, Dylan Schwaiger, Maël Zahaf, Thomas Cany, Ana Preda, Kara Matheu-Cambas, Thomas Morandini, Hugo Moreira Ferreira, Oscar Larfueille, Lucas Pilloud, Emilie De Palézieux Dit Falconnet, Lisa Girard, Sarah Carroz, Nadège Mouine and Milena Sommer.

At this moment of global political crisis, where the rise of the far right and illiberalism in the United States, Europe, and the Global South threatens democracy and our capacity to live together, it is essential to consider how architecture can pave the way towards new configurations of reality. These configurations must escape a binary, simplistic worldview in order to engage more fully with complexity. The issues that traverse our era – climate crisis, questions of identity, the place of truth, the importance and role of form – demand a commitment that speaks both to multiplicity and to the long term. Such a commitment must, therefore, engage with the fertile tension between specificity and universality.

In order to continue critically questioning architecture and reassessing it, both aesthetically and politically, in light of this contemporary context, we have this semester pursued our investigation of the concept of heterotopia as articulated by French philosopher Michel Foucault. We do not claim to do philosophy per se, but rather to understand how philosophical concepts can assist us in thinking through our own discipline and its expectations, when approached through an architectural lens.

Michel Foucault was a pioneering thinker in connecting planes of reality that had previously been seen as unrelated. He demonstrated that technical progress, modes of knowledge formation, morality, the measurement of time, the measurement of space, perception, and even the status of our own bodies were interlinked within our social organization. The study of their subtly intertwined evolutions illuminates previously unsuspected power dynamics, awareness of which now widely informs contemporary thought.

The concept of heterotopia, which he introduced in 1966 and which resembles constructed and localized utopias, pertains to the description of these previously unknown ensembles. As architects, we are interested in it for two primary reasons. First, because it defines a new category through the articulation of a criterion, in this case – the constructed utopia. This method mirrors architectural practice itself, which similarly benefits from revisiting known concepts or typologies by first stating explicit criteria. Second, because heterotopia lies at the immediate intersection of space, social organization, and collective imagination, thereby emphasizing the inherently political dimension of every architectural act.

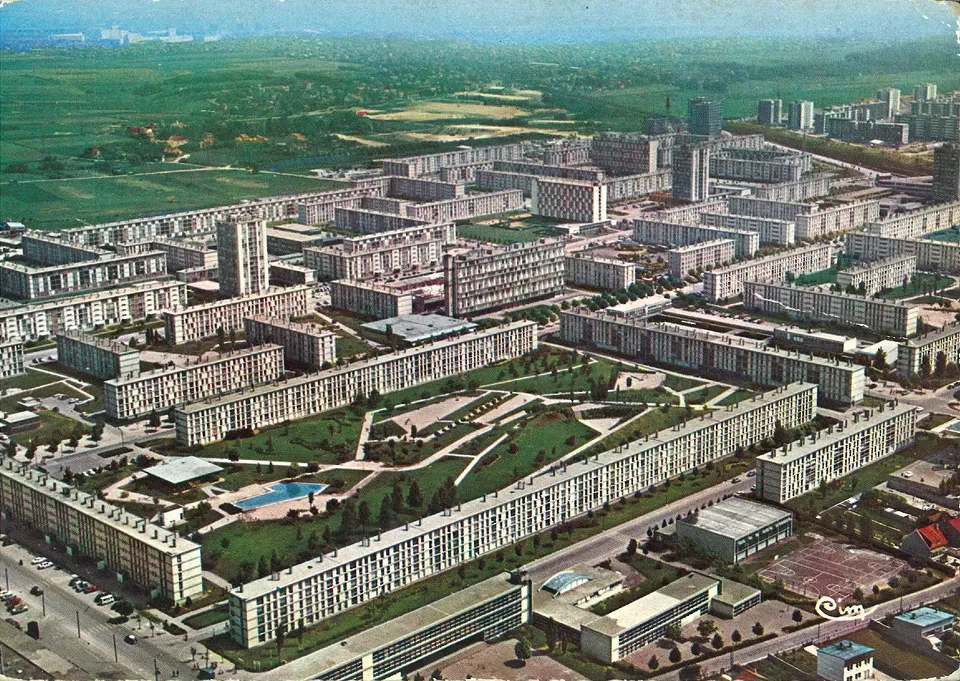

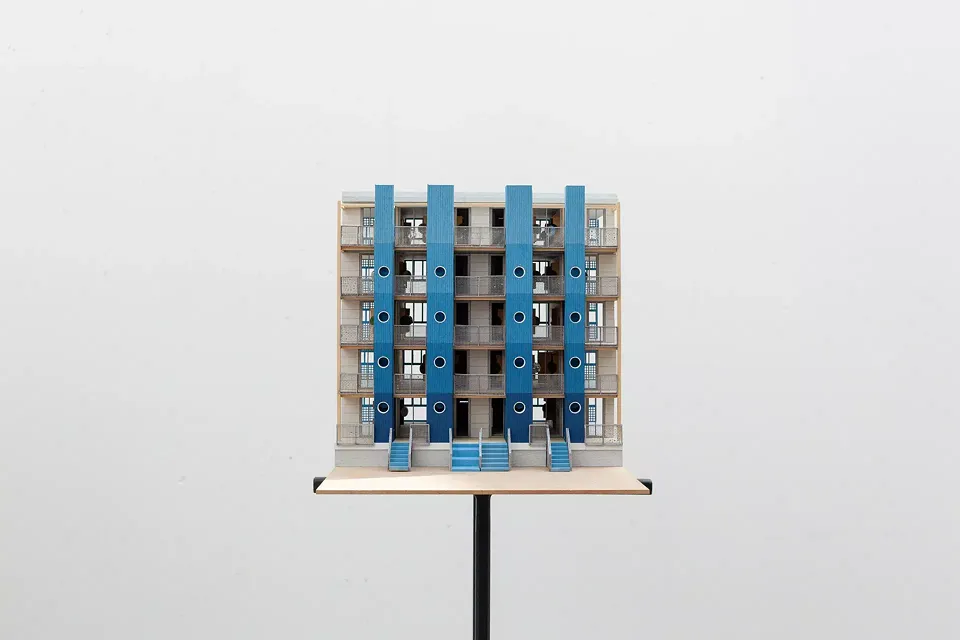

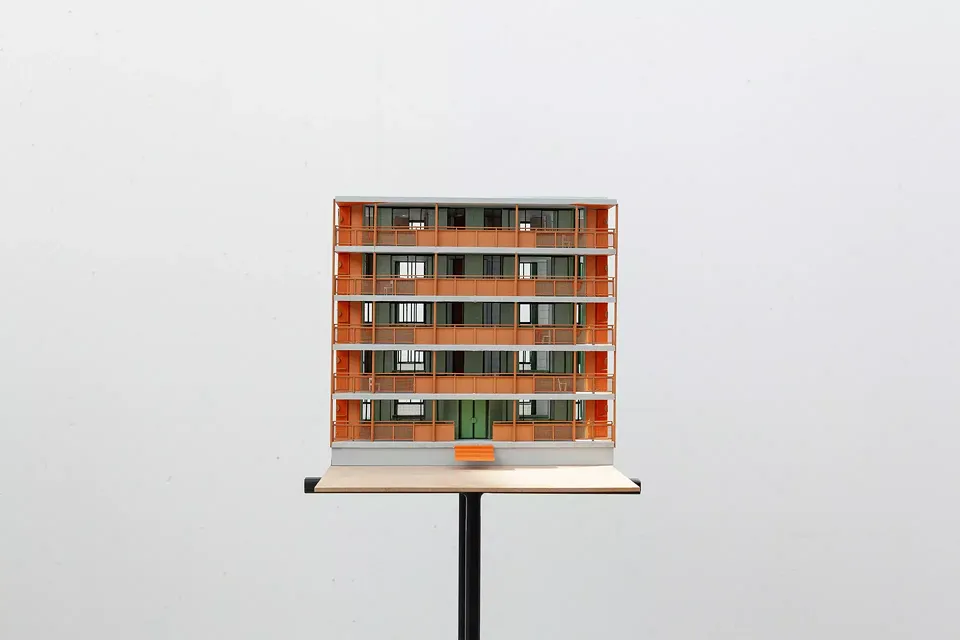

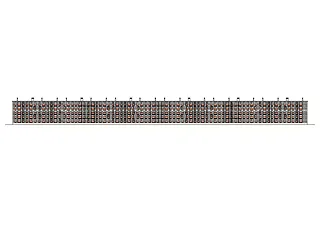

It is from this concept of heterotopia that we worked in the spring semester to envision the transformation of Sarcelles’s built substance. Indeed, Foucault’s concept resonates particularly well with this vast housing estate comparable in scale to a small city – consisting of 12'000 dwellings built over twenty years in the northern suburbs of Greater Paris. Both in terms of scale and the formal coherence of its various sections, Sarcelles stands out from many mass housing projects, which often typify dormitory towns, because it is a realized, living, polyfunctional, multicultural modern city constructed over time.

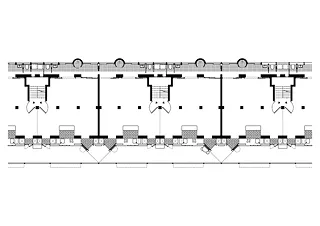

Project architects Roger Boileau (1909–1989) and Jacques‑Henri Labourdette (1915–2003) belonged to a tradition of modern architects – like Fernand Pouillon (1912–1986), trained under the pioneer of modern housing, Eugène Beaudoin (1898–1983). This tradition is characterized, singularly within the context of Modernity, by a keen interest in the precision of relationships between solids and voids, between buildings and the quality of the spaces they create between them, and a taste for well-defined spaces. Such qualities are found in Sarcelles, as in Pouillon’s housing complex “Point du Jour” in Boulogne, which Boileau and Labourdette completed after their mentor’s incarceration.

A careful attention to existing material and sensory qualities was the starting point of our design research. For many years, the French National Agency for Urban Renewal (ANRU) has overseen the redevelopment of large housing estates. Driven by a severe misunderstanding of the aspirations of the modern city – and blind to any recognition of its qualities or potentials ANRU has wielded demolition as a weapon, guided by a retrograde ideology and hostility toward modern architecture and urbanism. In Sarcelles in particular, it demolished stone‑built apartment blocks – the primary construction system of much of the city – and replaced them with isolated concrete slabs with external insulation, with no regard for the social or environmental costs of such a policy.

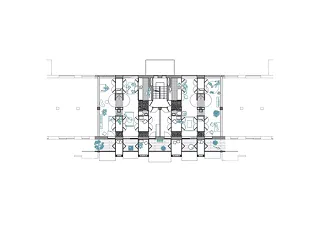

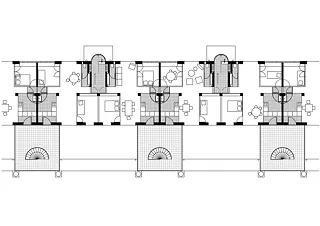

Our studio’s work clearly aims, as it did last year, to propose alternatives to demolition by expressing the full potential of these buildings and urban forms, without ignoring their limitations. The implementation of such alternatives serves both to celebrate the economy of means, without which no valuable work can emerge, and to preserve resources, emphasizing the cultural worth of these existing constructions as testimonies to an era when public authorities invested heavily to ensure everyone had dignified housing. We projected transformations that amplify the heterotopic character of the sites. Unlike in the first semester, when we envisaged housing for ultra‑specific communities, this time we aimed to conceive living spaces, with precise spatial organization and specific uses – but designed to benefit and address a broader public. In doing so, we reflected on the fertile tensions that arise between the specificity of domestic space and its capacity to accommodate as‑yet‑unknown inhabitants – an issue at the heart of housing design: «La maison à loyer est le lieu commun de l’architecture, lieu commun qui doit briller par le sens commun. Elle doit convenir à la foule, non à la façon d’une mode éphémère, mais à titre d’installation invariablement confortable et décente.» 1 wrote César Daly, a theorist of Haussmannism, in the mid‑nineteenth century.

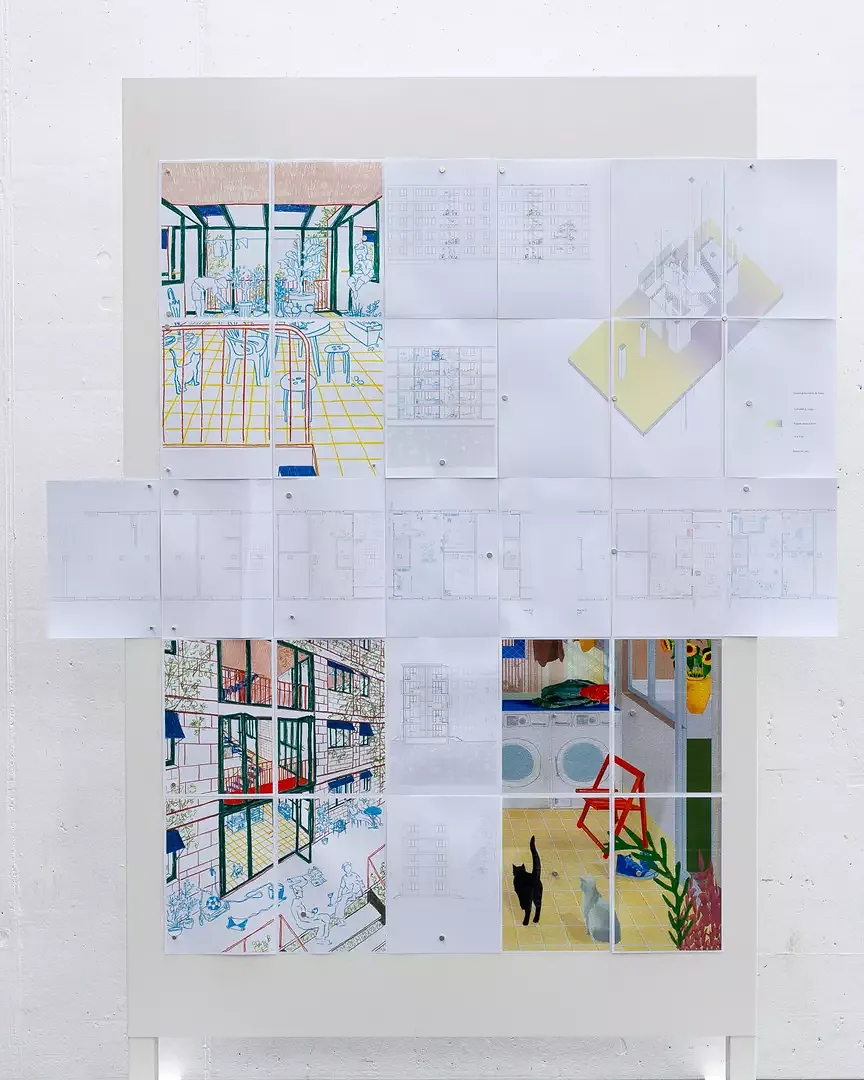

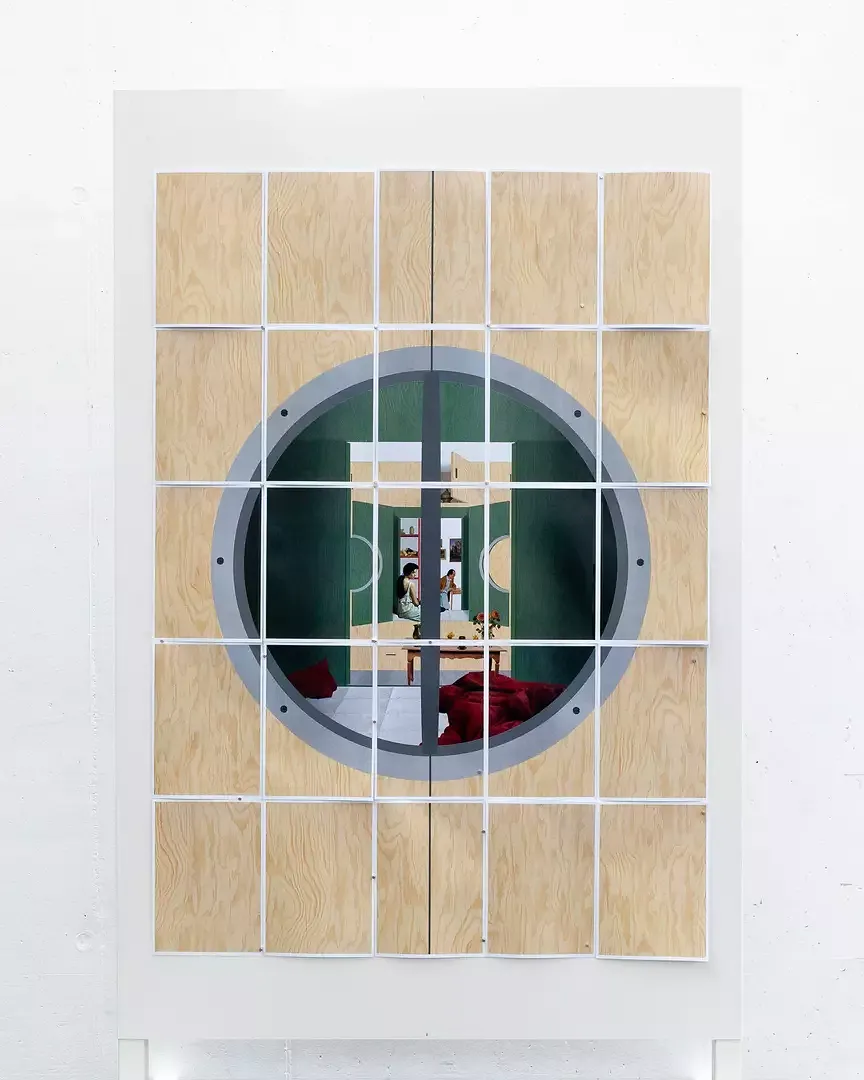

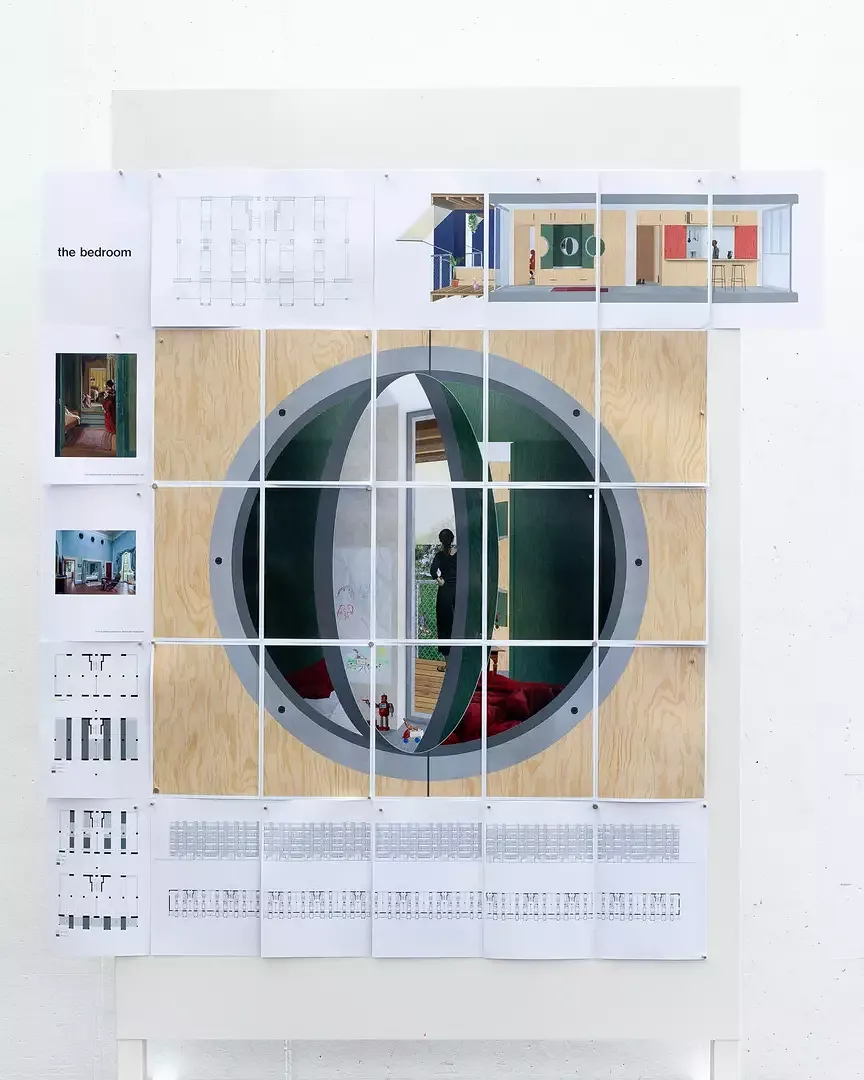

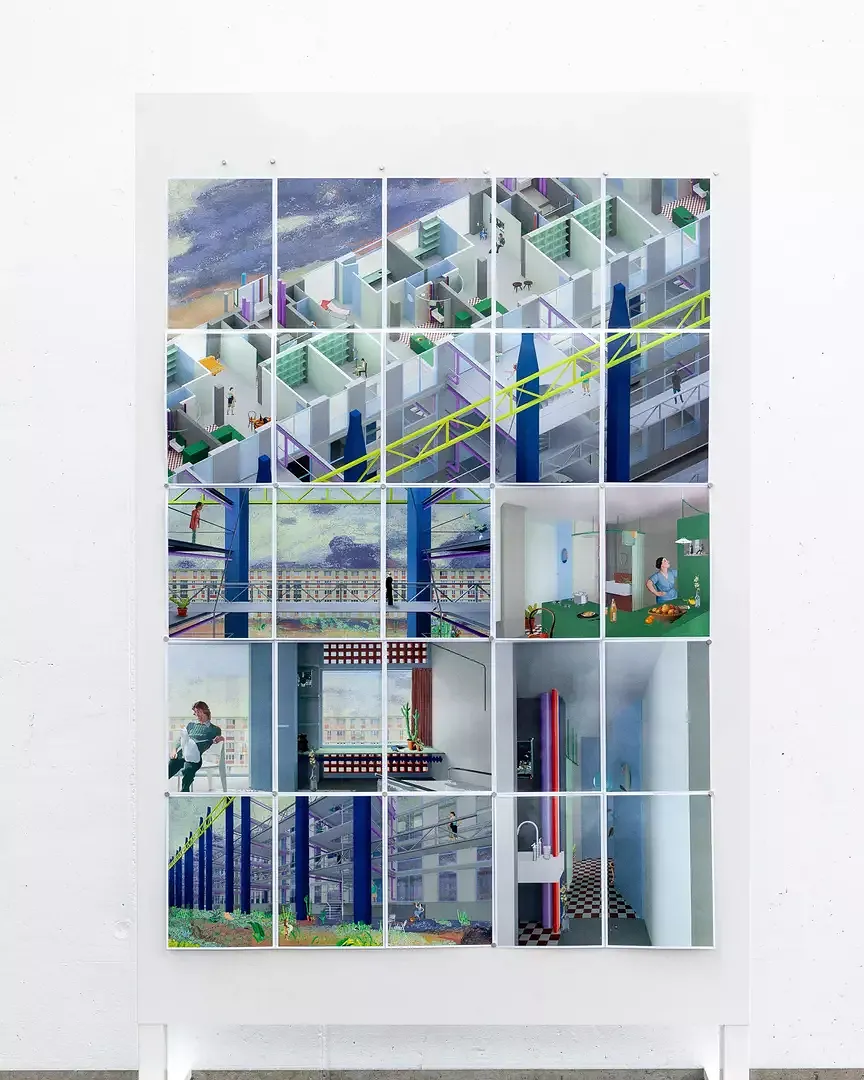

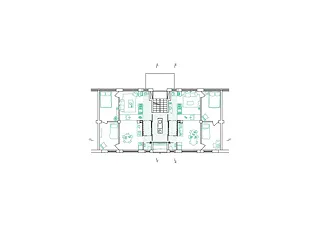

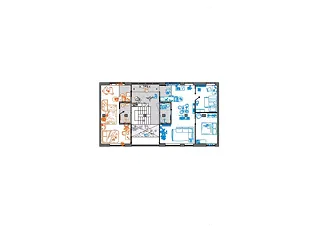

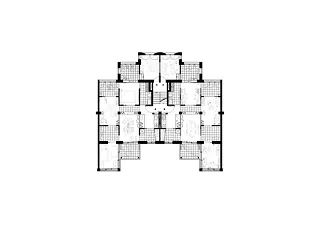

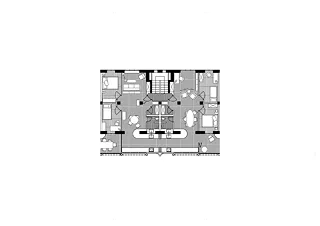

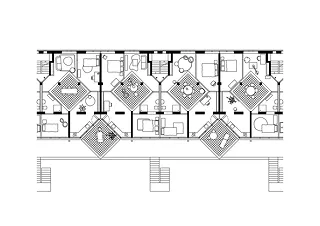

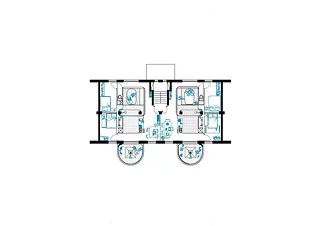

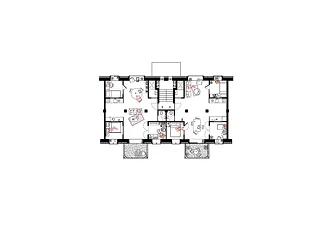

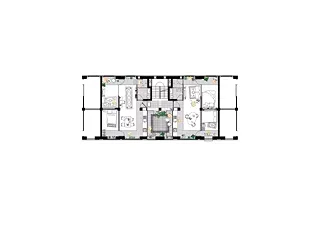

Concretely, we explored the hypothesis of a building transformed by the positive hypertrophy of one of its domestic uses. What would a dwelling primarily informed by the imagination and necessities of the bedroom look like? Or by those of the kitchen? The bathroom? The living room? And so on. But also, what would an entire building conceived according to such principles look like? A pretext to rethink, reevaluate and challenge the question of functionality or monofunctionality, and simultaneously to become more aware of the imaginaries and necessities attached to each traditionally conceived room. All of this intersected with life, housing use, and the familial structures that occupy them, etc.

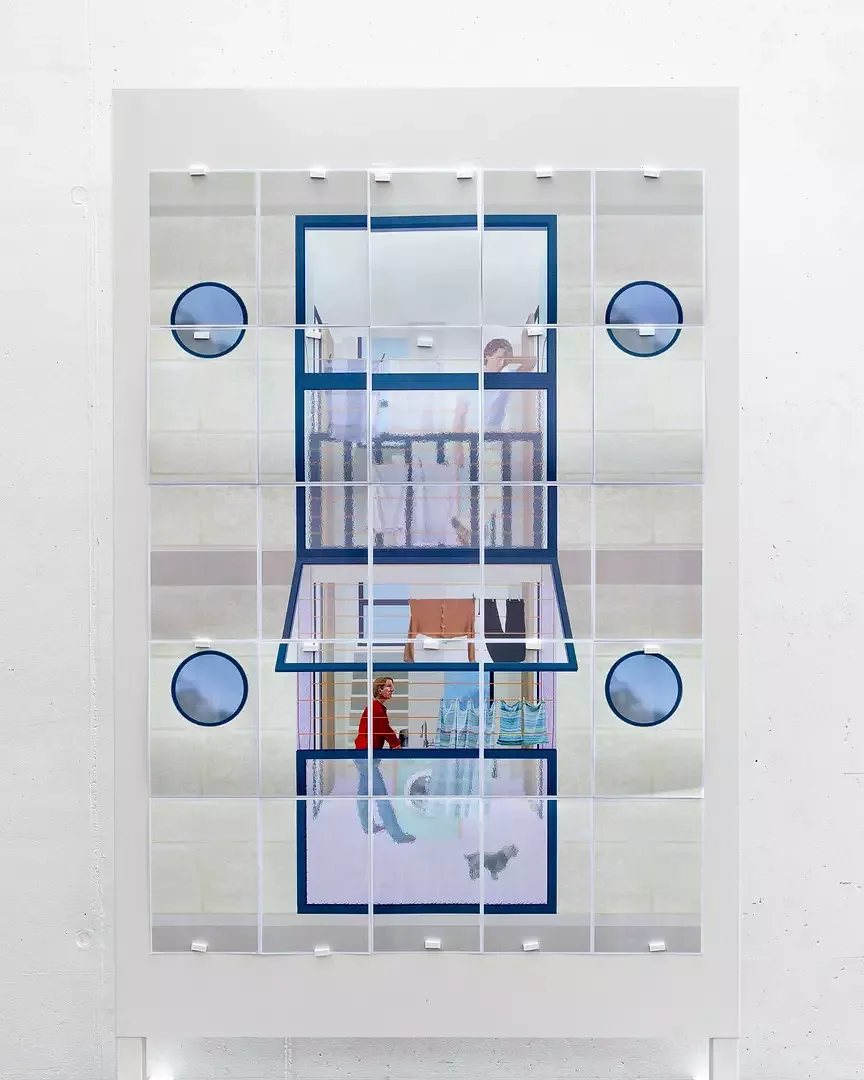

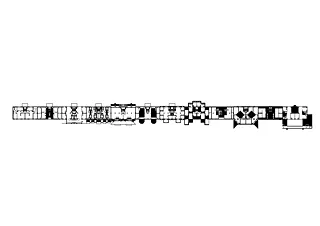

Thus, we envisioned the concrete implications of such changes through the study of a building representative of Sarcelles’s built substance – the northern block around Parc Kennedy – in order to establish new spatial, typological, and social standards. Each group proposed a transformation of this same block based on the imagination and necessities associated with their assigned room: the living room, kitchen, dining room, bathroom, bedroom, or laundry.

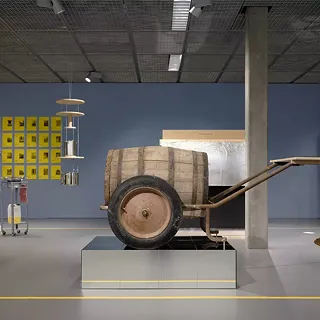

Finally and as initiated during the Fall 2024 semester, we developed a mode of project presentation that itself carries a heterotopic dimension: one that can condense space and time within a single medium and open architectural drawing to the movement of narrative. This presentation method relies on a simple, manipulable device: a series of A4 pages assembled into a grid. When closed, these pages form an initial unified perspectival image of the project, behind which unfolds a multitude of windows into different aspects of the work. These windows can themselves be opened, somewhere between a Russian nesting doll and an Advent calendar, multiplying viewpoints and offering additional spatial and temporal depth to this world‑architecture.

1 César Daly, L’Architecture privée au XIXe siècle sous Napoléon III, t. 1 et 2, Paris, 1864, p. 17.

The project by the EPFL Architecture Studio TEXAS was submitted for the Swiss Arc Award 2025 in the Next Generation category and published by Nina Farhumand.